COMMUNITY

MURALS MAGAZINE

SPRING

1986

The Chilean Cultural Exchange Project

By Lincoln Cushing

Text and photos copyright Lincoln Cushing

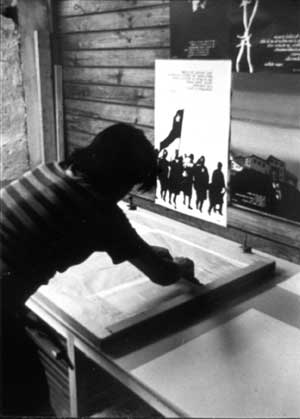

During the first two weeks of December 1985, I participated in a cultural exchange project with a community-based arts center in Santiago, Chile called Taller Sol. The goals of the project were to deliver art supplies, set up an exhibit of North American posters, construct a silkscreen printing workshop, teach a course in screenprinting, and return to the U.S. with documentation of current trends in progressive Chilean visual art.

The project was a collaborative effort by San Francisco Bay Area Casa Chile and Berkeley's La Peņa Cultural Center, both of which have maintained a long-standing relationship with Taller Sol. The trip was originally scheduled to take place in November of 1984, with at least one additional artist participating, but plans were cancelled at the last minute when a State of Siege was declared. By summer of 1985 we were informed that the situation was stable enough to make the trip worthwhile, and set a date for early December.

Costs of the Dictatorship

It has been more than 13 years since the coup, and conditions in Chile have changed dramatically over the past three years. The free-market economic theories of "The Chicago Boys" had been instituted with a vengeance: wages were frozen, tariffs and price controls eliminated, government subsidies to new industries ended, and social services cut to the bone. In mid-1981 Forbes magazine noted that the U.S. administration was "pointing to Chile as proof that the Reagan economic program is sound and will really work." As the Junta sold off previously nationalized industries, Chilean conglomerates (called "piranhas") bought them up with private loans. At one point, 60% of Chile's foreign debt was private. By 1982 everything was falling apart, the Junta had to intervene in nine key banks, and the "private" debt became public.

Today, Chile is faced with demands for $22 billion, the largest per-capita debt of any country in the world. This drain on the economy, coupled with an exorbitant military budget and unemployment of approximately 30%, has hurt so many levels of Chilean society that public opposition is overwhelming. The people have won many concessions through years of difficult work and suffering, and cultural workers have been central to that struggle.

Taller Sol and the Cultural Front

Taller Sol is a cultural center that was formed in 1978 by artists and musicians active in the resistance. It is located in a working-class neighborhood in Santiago adjacent to a Pena, a traditional Chilean music club and coffeehouse. Taller Sol has a small shop in front that sells crafts and several meeting rooms that are used for classes in music, dance, poetry and other arts. The rooms are also rented to neighborhoods and political organizations for various functions.

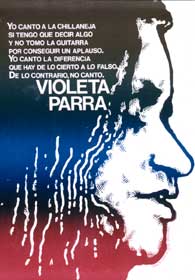

The center supports a small staff of about six people. Since politically active cultural workers are specifically targeted with a job blacklist, and other financial aids such as grants are nonexistent, Taller Sol generates virtually all of its income through street sales of postcards and posters. This is not an easy task; postcards sell for about 20 cents U.S., and an "expensive" silkscreen poster costs $2. No public function goes by without someone setting up a table or passing through a crowd hawking artwork.

Taller Sol is closely involved with CODEPU, the Committee for the Defense of the Rights of the People. CODEPU is the primary grassroots organization working aboveground that actively opposes the Junta's violations of human rights. Although it is not formally a coalition, it enjoys participation of every progressive church, labor and civic organization in the country. One of the main areas of work at Taller Sol is assisting CODEPU in its propaganda work, which includes such tasks as producing leaflets and painting stage backdrops for public programs.

Taller Sol is not alone in its mission. Several other organizations are involved with various aspects of cultural work. These include La Bicicleta, a literary and musical magazine which has been censored several times (and which has had to publish occasionally as a book in order to evade the more stringent magazine censorship laws); the Agrupacion de Plasticos Jovenes (APJ), which trains over 250 youth in visual arts and has produced over 8,000 square meters of murals; and the Centro Cultural Mapocho.

Generally these groups work under terrible material conditions. Basic supplies are expensive and difficult to get, training is hard to find, and facilities are. makeshift. One of the more prolific silkscreen poster printing studios I visited was on the second floor of a building that had been damaged in an earthquake; it had a roof but no walls.

The Artists

During my stay I had the opportunity to talk with many artists. The silkscreen class I taught included a good cross-section; it included a woman from the Youth Commission of CODEPU, a representative from CODEM (the Committee for the Defense of the Rights of Women), artists from La Bicicleta, three muralist/ printmakers from the APJ, a printmaker from the Centro Cultural Mapocho, several artists from neighborhood organizations, and independent artists. All these artists were very interested in art movements in the U.S., and were quite impressed with examples of posters I had brought as well as other artifacts such as the Syracuse Cultural Workers Calendar and Community Murals magazine. I also spoke of work such as the Shadow Project, the giant symbolic demonstration art by Bread and Puppet Theater, the poster distribution efforts of Northland Poster Collective, and the national organizing efforts of the Alliance for Cultural Democracy.

They in turn told me stories of surviving under the dictatorship. Almost every artist I met had some personal experience of repression, from having publications censored to being jailed and tortured. Between these extremes are tales of being beaten by police thugs after painting a mural to "relegacion"-internal exile to a remote section of the country where exiles must stay out of trouble and register twice daily at the local police station. This is a country where repression is such a constant that whole organizations exist for Families of the Disappeared, Families of Political Prisoners, and Families of Those in Internal Exile. It is clear that the dictatorship takes cultural work very seriously. I was moved by the enormous dedication and spirit of these artists, and touched by their appreciation of the Exchange Project.

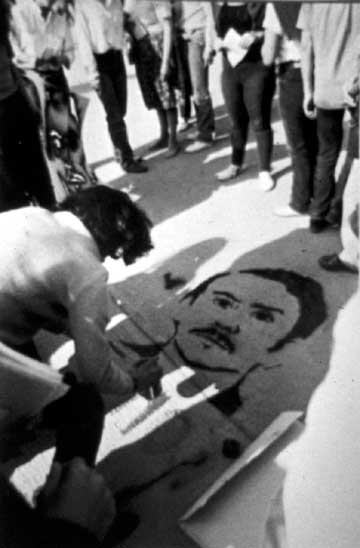

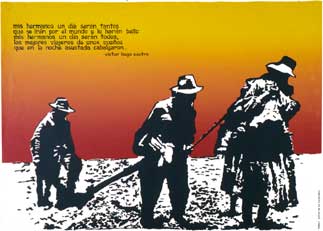

The Art

The diversity of artistic styles evident in current Chilean cultural work is striking. Posters and postcards presented images and poetry of predictable figures, such as Victor Jara and Pablo Neruda, but there were also popular images of Charlie Chaplin (the film "The Great Dictator" was a banned underground classic), John Lennon, and Geronimo. Murals have undergone a metamorphosis over the past twelve years. Early murals under the dictatorship were of a style well suited to guerilla production-one trained artist would quickly sketch outlines for an image and a hardy crew would simply color in the spaces. Although some of these early murals are still visible, most murals that I saw were painted in "secure" areas where more attention could be spent on developing artistic forms. Although the streets of Santiago contain lots of graffiti, most murals are found inside churches and in militant working-class neighborhoods.

One

"poblacion" I visited was La Victoria, about 20 minutes by bus on the

outskirts of Santiago. La Victoria has a long history of popular

resistance, and along the Avenida 30 Octubre I saw more than 15 murals

depicting a wide range of issues and displaying a variety of styles.

One series of three was done in one day (October 27, 1984) by a crew of

50, coordinated by the APJ. Each depicted a different theme-the

anniversary of La Victoria (this image was the second prize in a design

competition-first prize was a poster), an Homage to Political

Prisoners, and an Homage to the Fallen. This last one contains a

portrait of Andre Jarlan, a French priest who was "accidentally" shot

during a street demonstration in September 1984.

Although these murals are painted in a relatively protected area, the

State still takes notice. It is not unusual for the police or their

thugs to descend upon a mural site the following day and harass the

shopkeepers who provided the walls or beat up the muralists and their

helpers. A particularly disgusting brown paint is used to cover the

murals, but often they are cleaned up and repainted by the community.

Several murals bore evidence of repeated murder and resurrection.

Many other

media are used for public art. Elaborate stage backdrops are common;

these can range from murals on portable panels to huge sheets of

translucent plastic that are brightly painted with slogans and images

and draped several layers deep on a stage. Stencil images are also

popular for street art, often done in several colors and combining

images and slogans.

The Task Ahead

Popular resistance in Chile has reached new levels, and the task of rebuilding an active U.S. solidarity movement is urgent. The U.S. government under Reagan has behaved atrociously. For example:

A month after his inauguration, Reagan revoked a ban on U.S. government financing of exports to Chile through the Import-Export Bank.

The U.S. is no longer assisting in the investigation and prosecution of those responsible in Orlando Letelier's assassination.

The International Monetary Fund and the Inter-American Development Fund have lent Chile over a billion dollars.

The U.S. has opposed every U.N. vote critical of human rights violations.

Mrs. Reagan graciously received Mrs. Pinochet for tea at the White House while at the same time the State Department barred Hortensia de Allende from visiting the U.S.

Artists and cultural workers can help in many ways to reverse the harm done by our government. Chileans I met expressed a great need for material aid; art supplies can be sent directly to cultural groups that need them. There is also a tremendous need for basic professional communication; although there is a fair amount of travel between Chile and Europe, contact with the U.S. is much less frequent. Finally, many local Chilean solidarity organizations can benefit from cultural creativity. A nationwide boycott of Chilean goods is being organized, with other mass activities to follow.

Also see book review:

Democracy on the Wall: Street Art of the Post-Dictatorship Era in Chile

return to Docs Populi - Documents for the People

updated 4/23/2021

screenprinting at Taller Sol

poster by

"Arauco"

mural, La Victoria (working-class neighborhood in Santiago) -

"Wanted" (Pinochet)

street stenciling, Santiago; homage to fallen comrade Victor Zuņiga

mural, La Victoria

mural, La Victoria

poster by

"Arauco"