Safos

Safos

Lincoln Cushing, CounterSignals #5, May 2024

In Chicano graphics, C/S stands for “con safos,” meaning “with safety” or “with respect.” San Francisco Bay Area art activist and scholar José Antonio Burciaga (1940-1996) defined it as a barrio copyright – “don’t mess with this.”

But the mechanics of treating intellectual and artistic content with respect goes beyond “not messing with” something. Accurate cultural conception, the basis of our world view, relies on a host of subject specialties, most of which are unknown to the public. Oral history was a key part of that for most of human existence, and it was a respected skill to be able to accurately tell a long, complicated narrative in a compelling way. Visual art and published works have traditionally relied on trained librarians and archivists to collect, process, conserve, and share materials.

And just like any other human task, it’s political.

At every step of the way, decisions are made about allocation of resources, about the tradeoff between “good enough” and “best practice,” even about what one calls something. One of my heroes is public librarian Sanford “Sandy” Berman, who was a major voice during the long 1960s calling for reviewing and updating the Library of Congress subject headings. This “gold standard” for classifying documents was deeply mired in a male Eurocentric universe. Library activists pushed for, and succeeded, in making these search terms more respectful and more accurate. Berman’s 1971 Prejudices and antipathies: a tract on the LC subject heads concerning peopleis a classic C/S manifesto.

But as technology evolves, so do the battlefields. One of the biggest challenges now is the gap between analog content (such as books, flyers, and posters) and digital content. Whack on Google for anything and one gets an avalanche of returns – but think about what’s not there. A lot of digital content lurks in databases that require direct access, but that’s just a procedural limitation. What’s simply not there at all is material that hasn’t yet been digitized. Part of that is due to format – it’s a lot harder to properly digitize a 17x22” poster or an underground newspaper than an 8x10” photograph. And again, politics – mainstream content is more likely to get digitized than marginalized documents that “stick it to the man.”

I’ve been digitizing social justice posters for over 25 years. In the late 1990s this was a very clumsy process, requiring an outside vendor to scan Kodachrome 25 slides onto a Kodak CD. The “great yellow father” even made a simple digital cataloging application called “Kodak Shoebox,” referring to the common personal snapshot storage system. Clumsy, but transformative. For the first time one could assemble a cataloged collection of images on a computer and share it over the Internet. When I was finally able to shoot digital files directly I never looked back. I now maintain an archive of over 40,000 high-resolution poster images.

Yet images alone are relatively useless. To combat historical amnesia, we need to know who made that poster, when, where. The more catalog information we can assemble, the better. Cataloging is a political act. Fortunately, it’s now just bits and pixels, and can be updated and corrected. And once all this magic (another word for tedious work) happens, these documents can have a new life. I routinely get requests for this otherwise invisible content. Recently an author who needed 1969 Berkeley Liberation Program poster images for this publication, I provided three. Justseeds Artists’ Cooperative member Josh MacPhee emailed me, “You mention an interview [Cuban artist] Rostgaard did with Tokion magazine back in 2004, but their site is completely gone, and I can’t track it down via the wayback machine.” I found it in my well-organized physical files, scanned it, and sent him a PDF. Physical and digital archives working in harmony.

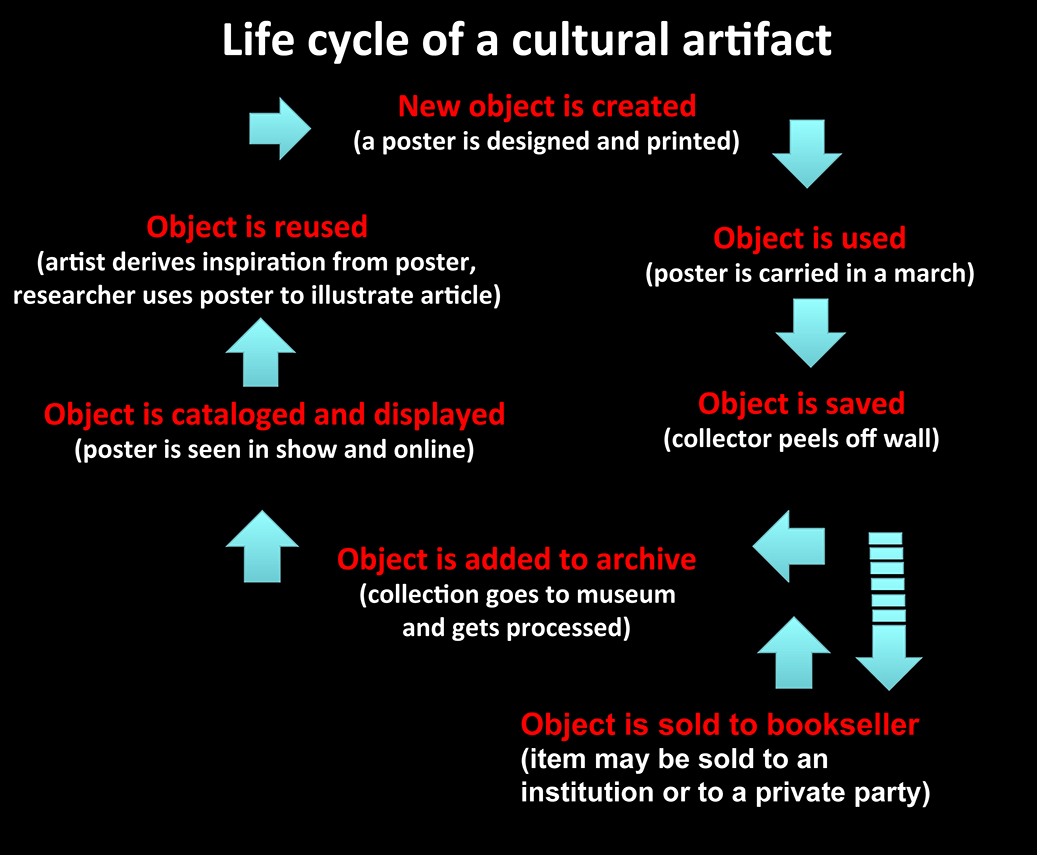

All of this has made me think about the ecology of content production and reproduction, and I’ve put together a flowchart to understand how all the parts fit. This is all a moving target, but based on the number of requests I get, it’s clearly a needed task. Other colleagues and comrades have taken up the challenge, and we are on the cusp of a research renaissance based on old material never readily available before.

Con safos, indeed.

Images:

C/S, detail from 1990 “MEChA presents 5 de Mayo Celebration” by José Antonio "Tony" Burciaga

Reproduction of digital image of an offset poster, 1990 “MEChA presents 5 de Mayo Celebration” by José Antonio "Tony" Burciaga

Life cycle of cultural artifact, Lincoln Cushing

Return to Docs Populi / Documents for the Public