![Rupert Garcia, "Fuera de Indochina! [reprint of 1970 poster]," 2000](Cuba_images/BAC10.jpg)

return to Cuban Poster Art

Late 20th Century Political Posters of Havana, Cuba and the San Francisco Bay Area

Exhibit at Berkeley Art Center,

September 28-December 13, 2003

Review in Berkeley Daily Planet

This exhibit was first conceived in the summer of 1990 after Chronicle

Books approached me to write a book. I was pleased that they were

willing to maximize its educational impact by producing a high-quality

book at an affordable price. I also committed myself to linking the

book to a public exhibit that would not only display these works as

artifacts but also explain them as cultural expressions. Berkeley Art

Center's Robbin Henderson readily agreed to hosting the show, so in an

unusual turn of events, the catalog was produced before the exhibit.

This is that exhibit.

This show consists of three linked parts. The first part, of course, is the selection of Cuban posters. The research and scholarship describing the posters, their artists, and their publishers - the Cuban Film Institute, OSPAAAL, and Editora Politica - is fully presented in Revolucion! Cuban Poster Art, and all sixty posters displayed here are in the book. The poster was the popular art form in Cuba following the Cuban Revolution, when the government sponsored some 10,000 public posters on a fascinating range of cultural, social, and political themes. From the 1960s through the 1980s, the posters rallied the Cuban people to the huge task of building a new society, promoting massive sugar harvests and national literacy campaigns; opposing the U.S. war in Vietnam; celebrating films, music, dance, and baseball. Many of these were also issues in the U.S. and other parts of the world, in a political and cultural blossoming that many of us knew simply as "the movement."

The second part is identifying and analyzing the "local connection" - the extent to which artists and political activists in the San Francisco Bay Area played a significant role in establishing dynamic solidarity links that deepened and enhanced the creative impact of both communities. On display are works by Bay Area artists Enrique Chagoya, Emory Douglas, Juan Fuentes, Rupert Garcia, Nancy Hom, Malaquias Montoya, Jane Norling, and Jos Sances, reflect the impact that Cuban graphics had on the posters produced in service to the movement during the 60s and 70s. The artist statements that accompany the posters help us to better understand this phenomenon.

The third part is of this show extends the analysis of this cross-fertilization dynamic. The text panel, accompanied by small poster reproductions, displays some of the mechanisms by which visual ideas fire up, get produced, and then get recycled back into that great collective hopper amusingly known as "original ideas." My role as curator has been informed by my role as an engaged participant, and it has always been clear to me that few non-artists understand how art, especially socially conscious art, is made. I hope that this exhibit helps explain some of the mechanisms of creative influence. Posters such as these have an enduring impact, and must not be seen simply as "nostalgic icons." Creative appropriation is the lingua franca of activists, and there is no shame in artful reinterpretation of powerful imagery. This is how they live.

Finally, as a librarian and archivist I believe it is crucial to insert the values of cataloging and documentation into the process. Artists must know the roots of their own imagery. Too little serious scholarly attention has been paid to recording our art - agitational, oppositional, movement, whatever label it may have. The tools available for digitizing, cataloging, and sharing visual resources are cheaper and more powerful than ever. For example, this exhibit includes 25 digital surrogates of Cuban posters. These reproductions were made from scans of bad slides (poorly shot and deteriorated) provided by Cuban publishers when no known copy of the original existed in their archive. This is the art equivalent of cloning dinosaur DNA. All of this was done on a shoestring budget and on volunteer time.

We have the tools, we must use them.

Lincoln Cushing, Docs Populi

This show

is dedicated to Warren Zevon, whose lyricism and inspired alliteration

never failed to lift my spirits.

In addition to the many artists represented here, I would like to thank

several people who helped make this show possible:

Robbin Henderson and Sharon Badillo of the Berkeley Art Center, for

agreeing to put the exhibit up in the first place; Alan Flatt,

Oakland-based collector and source of most of the ICAIC posters;

Michael Rossman, Berkeley cultural treasure and intellectual force

behind the AOUON poster archive.

Artist's Statements

Rupert

Garcia

poster displayed - "Fuera de Indochina!" [original poster

done 1970 for the Chicano Moratorium, displayed copy produced by the

Center for the Study of Political Graphics for 30th anniversary 2000]

As an art student during the strike at San Francisco State in the late 1960s, Rupert Garcia participated in the Art Department's student collective poster workshop and was aware of the posters coming out of Cuba. He used to purchase copies of OSPAAAL's Tricontinental at Modern Times bookstore, and included his first portrait of Che (1968) in his 1970 Master's show held at the alternative gallery Arte Seis (a precursor to the Galeria de la Raza) in San Francisco's Mission district. Although friends of his went to Cuba with the Venceremos Brigade, he himself never visited the island. He did make a pilgrimage to Mexico's Taller de Grafica Popular in the early 1970s and was deeply moved by the socially conscious artwork being produced there. Although Garcia usually practices his artwork as an individual, he holds in high esteem the collective and community-based efforts of such projects as Malaquias Montoya's Taller in Oakland and the MeChicano Gallery in East Los Angeles.

Garcia feels that it is very important to maintain an international solidarity aspect to his art - "It can be no other way." He also appreciates the Cuban posters because they maintain a high level of artistic and political power. "Both need to be taken to the same level," he believes. "Politics does not preclude the aesthetic."

-Lincoln Cushing interview with Rupert Garcia, September 19, 2003.

Rupert Garcia is an Oakland-based artist with numerous exhibitions and

publications to his credit.

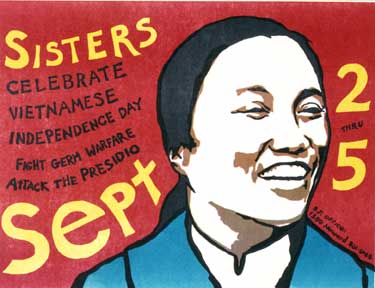

Jane

Norling

poster displayed - "Sisters - Celebrate Vietnamese

Independence Day - Fight Germ Warfare," 1971

They appeared on every wall in the San Francisco houses in 1970 where activists met in the struggle for civil rights/women's rights & against the war in Vietnam: the Cuban posters-vivid, clever, and compact-brought back by Venceremos Brigadistas from a tiny country in transition that taught us profoundly about liberation efforts around the world.

The posters themselves, largely from OSPAAAL (Organization of Solidarity of the Peoples of Africa, Asia, and Latin America), showed internationalism in imagery. With the sophistication of US corporate advertising, pulling design from Poland/China/Soviet Union, Cuban posters aimed content back at the monolith in a uniquely Cuban style that motivated me to use art for social change.

Cuban posters beautifully united art and politics-my fine arts education had emphasized their separateness-a union that launched countless small presses (no Internet) to agitate and educate. We redesigned Peoples Press in 1971 as a collective to write/design/print/distribute books/pamphlets/leaflets/newspapers/posters as publisher & community print shop. Suddenly my abilities as artist/book designer were needed in a way I couldn't have imagined as an earlier student of abstract painting. And-new concept-they were part of the means of production. Subverting the elitism of the art world, we placed design at the same level of print production as the press, camera, typewriter, layout tools. At the beginning we wanted all of us to practice all the trades of the shop, so I learned to print on the small press the posters I designed. Posters would not be signed because why should the artist/designer be named when the press operator went anonymous.

Peoples Press reprinted articles for North American distribution from OSPAAAL publication Tricontinental. In1972 I went to Cuba to work in the OSPAAAL design department and to study Cuban print production, but mainly for international cultural exchange.

Each issue of Tricontinental shipped with a poster folded into the magazine that illustrated solidarity with a particular people struggling against oppression. I was assigned by my responsible Alfredo Rostgaard to create a poster in the "Día de Solidaridad" series honoring the people of Puerto Rico. An interesting discussion arose about signing my poster. It never occurred to me to sign my OSPAAAL poster and Rostgaard couldn't imagine why I wouldn't sign it. His reason: The people want to know who the artist is. I'd come to Cuba thinking an artist was "bourgeois" to sign her work; in Revolutionary Cuba, artists/designers signed their work.

I am deeply honored to have had the opportunity to design a poster for OSPAAAL.

Since those years I've pondered the role of the artist as a named individual relative to the artist's work as it impacts society. The designer for the most part works anonymously producing items of visual communication under client/project banner-the product is what matters. The artist is named, name and person having everything to do with the artwork. Seems the terms are a function of purpose of the artwork; how well communication takes place is what matters.

My most effective artwork today, as it impacts society, are political signs, which enter the visual environment unsigned, unnamed. Curiously, they, more than any of my explicitly revolutionary artwork are, in design terms, the most direct formal line to my poster produced in Cuba 30 years ago.

Jane Norling provides graphic design & illustration for

social service organizations and for campaign for justice-electoral,

public health, union, cultural--and creates personal work in mural,

photo collage and paint media.

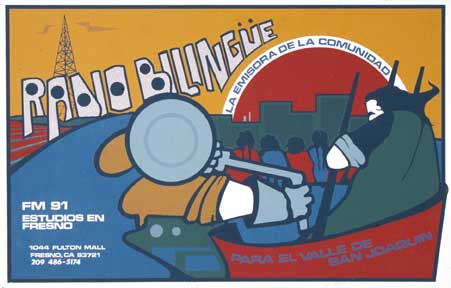

Malaquias

Montoya

poster displayed- "Radio Bilingue - FM 91 Estudios en

Fresno," 1976

I had done a poster, used as a fundraiser, for the first Venceremos Brigade, in 1971/72, I don't remember exactly. When the Brigade returned from Cuba, they brought with them, a set of Cuban posters. I believe it was a set of 21 prints that spoke of the revolution and I remember helping Karen Wald mount them for display.

I don't know if the Cuban posters influenced me, but I was certainly inspired by them, especially their use of color, their simplicity, and most of all their dedication. If I was influenced in any way, it had to be by their commitment to internationalism. For me, they made very clear, the importance of addressing issues of other struggling nations; that we all had one common protagonist.

As far as my work influencing the Cuban art scene, I have no idea, and it would be too grandiose a thought for me to think that I have. I'm just thrilled to have been a part of building bridges through my work with the various Brigades and exposing my students to Cuban art, being part of a committee to bring two Cuban artists to northern California in the 1980's, and a visit to Cuba as part of an educational exchange. Cuba's posters and graphic art have had an immense impact, not only in this country, but also all over the world.

It is important to note that my other "voice" is the poster/mural. I am much more articulate and able to express myself more eloquently through this medium. It is with this voice that I attempt to communicate, reach out and touch others, especially to that silent and often ignored populace of Chicano, Mexican and Central American working class, along with other disenfranchised people of the world. This form allows me to awaken consciousness, to reveal reality and to actively work to transform it. What better function for art at this time? A voice for the voiceless.

My personal views on art and society were formed by my being born into that silent and voiceless humanity. Realizing later that it was not by choice that we remained mute but by a conscious effort on the part of those in power, I realized that my art could only be that of protest - a protest against what I felt to be a death sentence.

As a Chicano artist I feel a responsibility that all my art should be a reflection of my political beliefs - an art of protest. The struggle of all people cannot be merely intellectually accepted. It must become part of our very being as artists otherwise we cannot give expression to it in our work. I am in agreement with Pedro Rodrigues, former Director of the Guadalupe Cultural Art Center, San Antonio, Texas, when he said, "Fundamentally, artistic expression, or culture in general, reaches its highest level of creation when it reflects the most serious issues of a community, when it succeeds in expressing the deepest sentiments of a people and when it returns to the people their ideas and feelings translated in a clearer and creative way."

Through our images we are the creators of culture and it is our responsibility that our images are of our times - and that they be depicted honestly and promote an attitude towards existing reality; a confrontational attitude, one of change rather than adaptability - images of our time and for our contemporaries. We must not fall into the age-old cliche that the artist is always ahead of his/her time. No, it is most urgent that we be on time.

Malaquias Montoya is a printmaker and teaches Chicano Studies

at U.C. Davis

Emory

Douglas

poster displayed - "Afro-American Solidarity with the Oppressed People

of the World," 1969

Emory Douglas first remembers seeing Cuban posters sometime in 1967 or 1968 when he was working on the Black Panther newspaper. In the early days the Black Panther Party official mailing address was Minister of Information Eldridge Cleaver's P.O. box, and they received newspapers and magazines sent from Havana. Douglas recalls being inspired by this revolutionary artwork from Cuba, Viet Nam and other countries. As a reciprocal gesture, the Party regularly sent newspapers, posters, and other mailings to Cuba. There was also direct contact as well - by the early 1970s Minister of Education George Murray traveled to Havana, and members from the New York and other offices served as a conduit for agitational artwork.

Very early on Douglas noticed that some of the posters coming from Cuba were appropriating his artwork, and true to the spirit of the times he was "Glad to see it picked up." Douglas himself never got the opportunity to travel to Cuba - "Chores for putting out the paper always seemed to be more important." He also did not get the chance to visit with any Cuban artists who traveled here, although he have liked to. To this day, as he gives lectures and slide presentations about his work, he acknowledges the impact of the Cuban artwork and is proud to have played a part in the visual arm of movements for social justice. When reflecting on the images from that period, he notes that one needs to remember the social context at the time to understand what may be seen as a culture of violence. "Look at the 10 Point Program." he says. "It explains why people were doing what they were doing."

"7. We want an immediate end to police brutality and murder of black people. We believe we can end police brutality in our black community by organizing black self-defense groups that are dedicated to defending our black community from racist police oppression and brutality. The Second Amendment to the Constitution of the United States gives a right to bear arms. We therefore believe that all black people should arm themselves for self defense." -Black Panther Party Program, October, 1966.

-Lincoln Cushing interview with Emory Douglas, September 19, 2003

Emory Douglas is a revolutionary artist and an illustrator, and was involved with the Black Panther from the very beginning. He was production manager from its third issue in 1967 until its last in 1980, and now does production work for Sun Reporter Publishing in San Francisco.

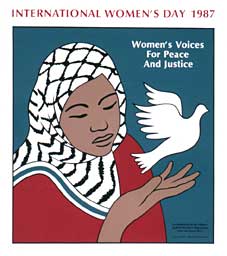

Nancy Hom

poster displayed - "Carnaval," 1981

The political climate of the 1970s influenced my development as an artist. I became interested in community events and Asian American history after participating in anti-Vietnam War demonstrations. I was drawn to the posters that were coming out of Cuba at the time, especially those of René Mederos, whose work was popularized in the United States through offset reproductions of his images. Almost every Asian American activist I knew, including myself, had his "Vietnam Will Win" poster depicting Ho Chi Minh quietly reading by the river.

The flat graphic depictions and brilliant colors of the Cuban posters appealed to my sense of aesthetics. When I was introduced to the silkscreen medium at Kearny Street Workshop, a San Francisco based multi-disciplinary Asian Pacific American arts organization, in the mid 70s, my posters reflected this bold flat style and use of bright colors as well. Like many of the Cuban artists, I preferred to let a single image represent the emotional content of the work. I also favored patterns in my art, like that used in René Mederos' "12th Anniversary of the NLF of South Vietnam" poster and Antonio Mariños "Day of Solidarity with Guatemala." Some of my work made use of high contrast imagery, as in Ernesto Garcia Pena's "The Chilean People Will Smash Fascism" and René Mederos' "I'm Going to Study to be a Teacher."

Since I created my first silkscreen image in 1978, I have devoted my career as an artist to the non-profit sector, creating artwork for numerous political, social, and community events. Like the Cuban poster art, much of my work has celebrated community cultural events, such as festivals, dance, music and theater. I have also created posters to promote better health care in inner city neighborhoods, and images of solidarity with women, political prisoners, and other struggles here and abroad. The art that came out of Cuba in the 70s and 80s has inspired me in subject matter and informed my aesthetic decisions for over three decades.

Nancy Hom is a printmaker and former director of the Kearny Street

Workshop in San Francisco.

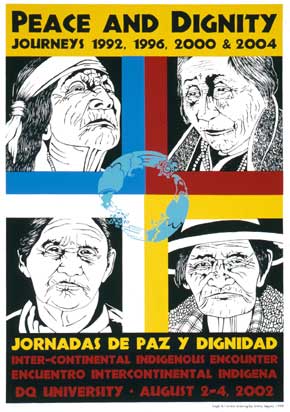

Juan

Fuentes

poster displayed - "Peace and Dignity -Journeys 1992, 1996,

2000 & 2004," 2002

In 1975 I traveled to Cuba as a member of the Venceremos Brigade. During our stay we helped build homes just outside of Havana. We also traveled all over the island visiting schools, factories, and farms. There were bold and colorful billboards and posters proclaiming national identity that addressed cultural, social, and political themes. It was here that I began to see the powerful impact these images provided to society.

Political activists were collecting Cuban posters. The ones that had the greatest impact, for me, were the posters done for OSPAAAL, with messages and images of solidarity with the liberation movements of the third world. These silkscreened and offset prints became my inspiration for the posters that I would later create.

In 1975 Susan Adelman and I organized the first west coast exhibit of Cuban posters at the California Palace of the Legion of Honor in San Francisco. Later that same year the posters were exhibited El Centro Cultural de la Gente in San Jose, California and at the ASA Gallery in Albuquerque, New Mexico.

Two years ago, as Director of Mission Grafica, I organized a cultural exchange between the Mission Cultural Center for Latino Arts and Cuban artists. I traveled to Cuba to co-curate the exhibit created by Bay Area Latino artists.

En lucha,

Juan R. Fuentes, 2002

Juan Fuentes is a printmaker and art instructor living in San

Francisco.

Jos

Sances

poster displayed - "U.S. Hands off Cuba Exhibit," 1990 (with

Enrique Chagoya)

My love affair with Cuban posters began in 1981. I know this may seem late by left revolutionary standards, but I was young and foolish, I'd overlooked the roots of an art form that later would become my life. The Mission Cultural Center in San Francisco, where I had just begun working as a screenprinter, sponsored a show of Cuban printmakers primarily featuring the work of Eduardo (Choco) Salazar and Nelson Dominguez. This show blew my mind. I was really impressed with the completely liberated way they created prints, collaging with any element, scratching, tearing, splashing all coming together to create this very concise yet unbelievably loose image. I have a screenprint made for the '81 show by Nelson; its lilac-to-creme split fountain background is very unusual, almost like a Japanese block print. Are his drawn doves internal or external? Are they a burden on the head or its liberator? The circle template, paperclip texture becomes hands and shirt. This art sunk deep and it affects the way I make art to this day.

For none of the above reasons my favorite Cuban poster maker is Eduardo Bachs, his cartoon style and very strong graphic sense always grabs me. His humor is an incredibly stealthy tool and serves as a reminder of how to use graphics to communicate. While none of the art I create would make anyone think of Bachs, his sense of humor is something I have tried to emulate. His ability to turn a butcher/dictator like Pinochet into a clown and make us laugh at the same time is pure genius.

During my seven years at the Mission Cultural Center scarcely a day went by when we didn't do something that had a Cuban flavor. Working in the Central America solidarity movement, Cuban issues, Cuban artists and even Cuban rum (Cuba Libre) were constant companions. It's practically impossible to even think of those years without thinking about Cuban posters.

In the mid-80s I reproduced an edition of Ché posters by Raul Martinez. While I did not deal with Raul directly, (it was done through German curator Reinhart Schultz), I found it very funny reproducing the work of someone I believed changed the way people thought about Viet Nam. Everyone I knew who was against the war, it seemed, had his work on their walls (Maybe some of them were René Mederos' too). It was posters like these that influenced my decision not to fight in that war. While I'm not stylistically attracted to Raul's work I have come to fully understand the cumulative power of the messages his posters deliver.

Finally my relationship with Cuban posters was reignited through Lincoln Cushing. It was the mid-90s, all the Cuban baseball players had defected, the boatlift happened, the collapse of the Soviet Union and all the revolution gone to shit. And along comes Lincoln with his Cuban poster archive and he wants me (Alliance Graphics) to make these Cuban sports posters into tee shirts. Beautiful work by Luis Alvarez and Jesus Forjans. And all of a sudden I'm seeing past Nike billboards and Christian Dior ads, remembering there is a place beyond the consumer rainbow and past the darkness of the "have nots." I was reminded why I fell in love with these posters in the first place. Thanks Lincoln.

Jos Sances is a screenprinter, painter, sculptor, and all-round artist.

He is the designer-in-residence at Alliance Graphics.

Enrique

Chagoya

poster displayed - "U.S. Hands off Cuba Exhibit," 1990

(with Jos Sances)

I discovered the art of Cuban posters in the early 70's when I first saw them in person in the houses of friends in Mexico City and later in an edition by McGraw-Hill with an introduction by Susan Sontag. Since then my perception of political art was completely transformed. The State sponsored political art of muralism in Mexico and the "Socialist Realism" coming out of the socialist countries was dry and dead in comparison with the freshness and inventiveness of the Cuban posters from the early years of the Cuban Revolution. My favorite ones were the film posters for the Cuban movies we used to watch at the university film clubs in Mexico. Today, whenever I see them, they bring me some nice flashbacks of those wonderful and intense post-revolutionary years, and remind me that much injustice and corruption remain to be abolished.

Enrique Chagoya is a printmaker and art instructor.

return to Cuban

Poster Art