Sidewalk Stamps

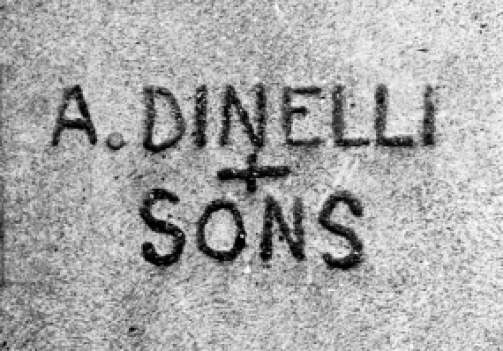

These stamps date back to the late 1800s, when sidewalks of stone, gravel and brick began to be replaced by the new material known as "artificial" or "art" stone. They are essentially advertising, and some even include phone numbers and full business addresses. Most, however, just include the contractor name, the name of the city in which the business was registered, and year the stamp was set.

The stamps always identify the cement mason, either by company name or by union. Some stamps are very simple, not much more than hand-written, others mimic the oblong shape of printing union "bugs," and a handful display elaborate artistic flourishes.

Building and Construction Trade stamps

Some stamps reflect not the just contractors, but the trades that represented them. In front of Berkeley’s Virginia Bakery and at Freight and Salvage one can find the distinctive crossed tools mark of the earliest union stamp, that of the American Brotherhood of Cement Workers (ABCW, 1903-1913), [photo] whose president was Olaf Tveitmoe. Olaf was a classic colorful California labor leader hero of his time – both a working-class heavyweight who got elected to the San Francisco Board of Supervisors as well as first president of the racist Asiatic Exclusion League in 1908. The Constitution and By-laws of the Cement Workers’ Union Local No. 1 A.B. of C.W. (1912) clearly sets the tone for the protectionism of the period:

“Qualifications of Membership.

Section 1. All white male persons of good moral character employed at cement work, not less than twenty (20) and not more than fifty (50) years of age, citizens of the United States, may become members of the Union, as hereinafter provided.”

A major jurisdictional struggle over which union could represent the workers in this segment of the building and construction trade came to a head in 1912. A rival union, The Laborer’s International Union of North America (LIUNA, more generally referred to as “The Laborers”) which was originally founded in 1903 as the International Hod Carriers’ and Building Laborers Union of America, had been aggressively encouraging its members to accept the changing technology represented by concrete: “Don’t say concrete is a failure. Don’t say brick or stone is superior, but organize and combine to control concrete construction good, bad, or indifferent. Let us control the labor end of the proposition.”

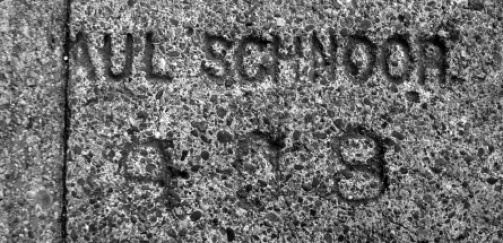

The Laborers applied to the American Federation of Labor for a charter amendment giving them full jurisdiction over “Common Laborers employed in the mixing of concrete” and changed their name to the International Hod Carriers’, Building and Common Laborers’ Union of America. In a landmark case before the A.F.L. Executive Council, the A.B.C.W. was directed to turn over all laborers employed in that industry to the Laborers. By 1915 all workers in the trade were either represented by the Laborers or by the Operative Plasterers' International Association, which changed their name in 1914 to the Operative Plasterers' and Cement Finishers' International Association because of the large influx of workers in that portion of the trade. Many examples of union stamps belonging to the OPCFIA are evident in California. Their distinctive label not only includes the Local number (“594” is the East Bay), but also proudly notes by number the Master finisher who did that piece.Sources:

Official Journal of the International Hod Carriers’ and Building Laborers Union of America, March, 1907 (cited in The Laborer, 100th Anniversary Edition 2003, LIUNA, page 33)

http://www.opcmia.org/ , “our History” section.

.